This article was first published on December 31, 2021 as an exploration on the origins of Champagne and its ascendance as the preferred drink for weddings, celebrations, and New Year toasts. It seems at home as part of the Table Talk series that we debuted in 2023 as a medium to discuss anything from kitchen innovations to what’s on the shelves of your pantry. I think it pairs nicely with a glass of Veuve Clicquot, or your favorite sparkling wine.

On Christmas Eve, I ordered a glass of Veuve Clicquot Yellow Label Brut Champagne specifically because the tasting notes suggested notes of apricot, vanilla, toffee apple, and toast; I wanted to taste it myself. As promised, it was “a balance of strength and silkiness” that not only paired beautifully with my truffled beef carpaccio, but also was the ideal beverage with which to toast my beloved spouse.

I’m not confident that I would have ordered my own glass of champagne (or sparkling wine) if my curiosity wasn’t piqued while reading The Widow Clicquot: The Story of a Champagne Empire and the Woman Who Ruled It by Tilar J Mazzeo and wondering what all the fuss was about. I drank sparkling wine at wedding receptions, graduation ceremonies, and for the odd celebratory toast but it didn’t taste all that special to me other than “fizzy wine.”

My curiosity led me into an exploration about the history of champagne and why we’ve come to cherish it so much. In researching, I also did some tasting and discovered the joy in trying different sparkling wine and champagne variations, vintages, and of course terroirs.

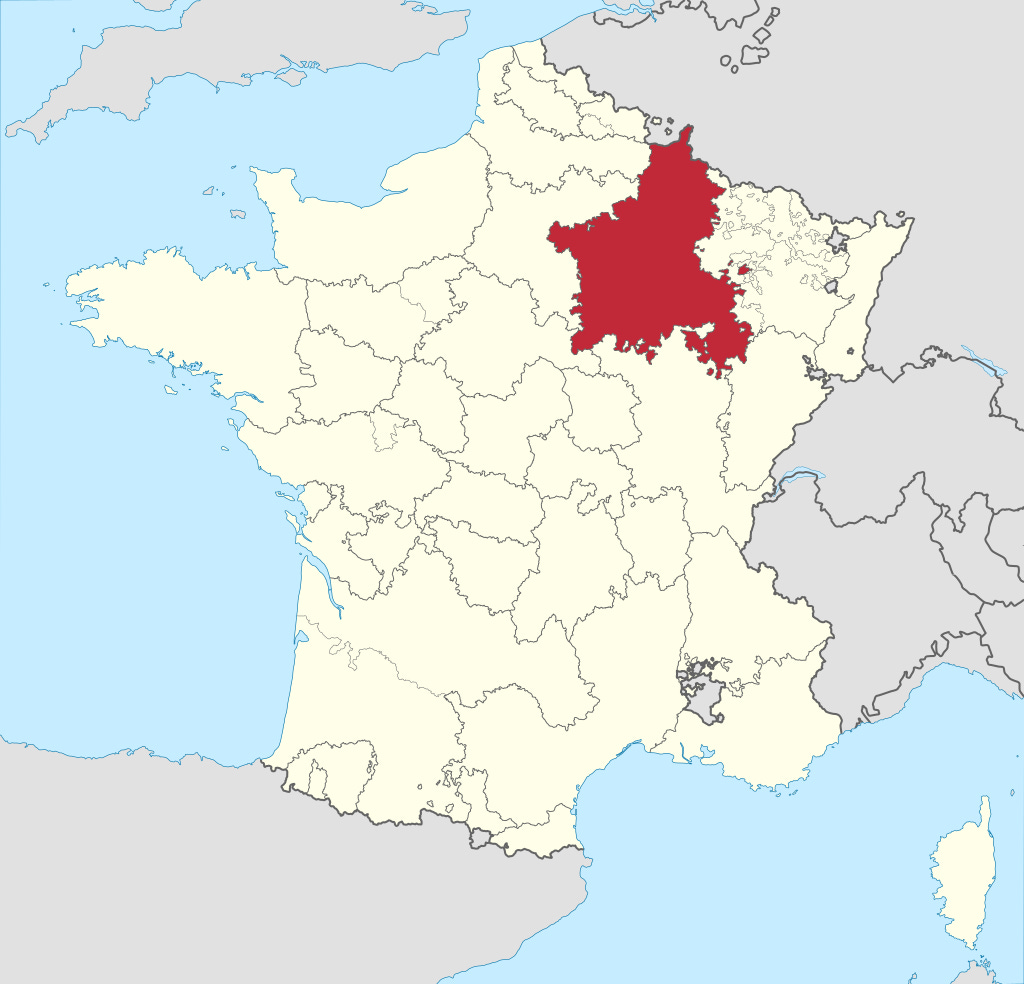

Bubbly, sparkly, effervescent – champagne is practically the official toasting drink of weddings, celebrations, and New Year’s Eve. Much is well known about the pale wine that hails from the unique terroir of northeast France, such as that the beverage must originate from the Champagne wine region to be legally called champagne, or else it is merely sparkling wine.

But there are more than a few twists in the story of champagne’s origin to amuse you while waiting for the ceremonial New Year’s Eve ball to drop –

Champagne Wine Production Started as a Turf War

It was the ancient Romans who first saw the region’s potential for viticulture, and the region has been cultivated at least since at least the Fifth Century. However, the Pinot Noir of the Champenois were light-bodied, pale, and thinner than the rich Burgundy wines of southern France. Pressure to produce acclaimed wines mounted when the coronation of Hugh Capet as “King of France” in 987 at Reims created a grand tradition of lavish coronation banquets featuring local wine.

A Beautiful Accident

Viticulture was challenged by the northerly climate; grapes struggled to fully ripen plus cold winter temperatures halted wine fermentation in cellars. Warming spring and summer temperatures caused dormant yeast cells to restart fermentation, with the side action of producing carbon dioxide gas. Many fragile glass bottles of wine exploded under the pressure, but those that survived often contained bubbles of carbonation, a grievous fault by winemaker standards.

French Benedictine monk Dom Pérignon, an influential scientist in the production of quality of Champagne wines in the late 17th Century, conducted several experiments in a concerted effort to prevent refermentation. Many of his techniques for pruning and harvesting grapes and blending grapes from several vineyards prior to press are part of wine-making rules to this day.

Blame it on the British

For all its historic might, England lacks winemaking resources and has the endearing habit of embracing French styles, foods, and fashions. Marquis de Saint-Évremond introduced still wine from the Champagne region to British royalty and aristocracy and wine imported in wooden barrels across the English Channel faced the same refermentation issues turning still wine into sparkling wine. Without the stigma that bubbly wine faced in France, champagne was embraced and became extremely popular among wealthy elites.

Back in France, Philippe II, Duke of Orléans began his regency and pushed acceptance of champagne to new heights. Several major champagne houses were founded during the 18th Century to capitalize on this craze, including Veuve Clicquot, Moët & Chandon, Louis Roederer, Piper-Heidsieck, and Taittinger.

While the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars put a dent in champagne sales, nobles fleeing France for the safety of Eastern Europe had the opportunity to blend their champagne wishes with caviar dreams and before its Revolution of 1917, the Russian empire was the second largest consumer of champagne in the world.

The Cost of War

World Wars nearly ruined the champagne wine industry as vineyards, warehouse, and production facilities were destroyed. Some underground crayères (limestone caverns) protected wines and people alike from artillery bombardment, but the region was devastated – by the end of World War I, the Champagne region lost nearly half its population. From chaos grew the groundwork for the future Appellation d'origine contrôlée (AOC) system that defines winemaking rules and protects the champagne brand.

The region fared slightly better through World War II but saw sales to the United States and Russia decline due to the one-two punch of the American Depression and Great Prohibition, and the Russian Revolution. Still, with six cases of vintage champagne, Germany’s unconditional surrender was celebrated on May 7, 1945.

Some “Legends” are Clever Marketing

Sorry to burst your bubbles, but there is also a fair amount of champagne lore that just isn’t true.

Alas, Dom Pérignon neither invented champagne nor uttered the beautiful saying: “Come quickly, I am tasting stars!” That quote dates to a printed advertisement in the late 19th Century.

Another famous champagne legend is that the form of the champagne coupe glass – known by its shallow, broad-based saucer - was modeled after the left breast of French queen Marie Antoinette … or maybe one of the famous “maîtresse-en-titre” (royal mistress) Madame de Pompadour or Madame du Barry. Truth is that the glass shape originates from England circa 1663; it was fashionable for serving champagne in France until the 1970s and in the United States from 1930s to the 1980s.

And while some believe that it is good luck to toast in the New Year with champagne, the tradition likely just stems from the belief that having a glass of the “good stuff” will invite prosperity into your life, and there’s nothing wrong with that.

Let’s Stay Connected

Follow us on Instagram @asweeat,

Join our Family Recipes, Traditions, and Food Lore community on Facebook

Subscribe to the As We Eat Journal

Listen to the As We Eat Podcast

Do you have a great idea 💡 for a show topic, a recipe 🥘 that you want to share, or just say “hi”👋🏻? Send us an email at connect@asweeat.com

Looking for a unique gift idea for a birthday, anniversary, holiday, host or hostess, or just because? Consider giving a subscription to the As We Eat Journal.